Reprint of the article “Volunteers Defy US Policy on Nicaragua.” Boston Sunday Globe, February 2, 1986. Boston, MA: The Boston Globe.

Volunteers Defy US Policy on Nicaragua

By Ross Gelspan, Globe Staff

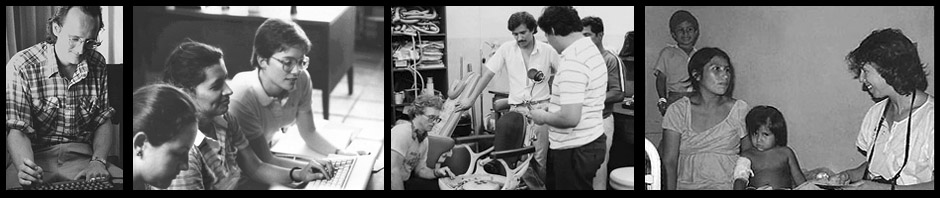

Cambridge — Nearly 200 American volunteers with expertise in technical fields are defying US policy by working in Nicaragua despite an economic embargo imposed by the Reagan administration.

The group, called TecNica, includes machinists, computer scientists, seismologists and engineers who spend their own money and vacations to repair hospital equipment and electrical generators, install computers and rebuild vehicles in one of the poorer countries of the world.

“Basically we’re tapping a motive in people—most of whom are not especially political—who want to use their skills to do something with purpose and meaning,” explained Michael Urmann, 41, a former economics professor from California who founded TecNica in 1983.

To date, Urmann said, the group has provided the equivalent of about $1.5 million in expertise, training, and materials aid.

Train Nicaraguan Workers

Volunteers typically spend two weeks in Nicaragua working on development projects and training Nicaraguan workers in the use of machinery and technology, said Charles Welch, a research engineer at MIT who heads the local TecNica office.

When they return, the volunteers write summaries of their work and of other potential projects, so the next round of visitors will be prepared to continue the work, Welch said.

During a presentation at MIT last week, one machinist, who worked at the Ministry of Construction in Managua, said that to repair government vehicles, workers in Nicaragua must make bolts and nuts by hand. Unable to buy replacement parts for American-made machinery, Nicaraguans make wooden models of the parts, then cast them by hand in sand molds before finishing them, he said.

Craig LeClair, a communications specialist with the Cambridge firm of Bolt, Beranek and Newman, recently spent two weeks in Managua where he helped design a network linking a central computer in the capital with others in outlying regions.

“In one office, I found workers randomly inserting various discs into a computer to get it started. Because they had no instruction manual, they didn’t know how to load a Lotus program into the computer,” he said.

Despite the country’s poverty, LeClair said he was impressed by the pragmatism and energy of Nicaraguan officials, many of whom are under 40. “They are willing to try anything you suggest. And there is not the kind of stifling bureaucracy you find in other places,” he noted.

What Volunteers Do

While TecNica has no position on US policy in Central America, Welch noted that some volunteers have become politically active as a result of their experience.

John Leek, a machinist at Boston University, spent part of January near the Honduran border to help repair a hydroelectric generating facility. The facility was surrounded by three huts manned by armed militia members to guard against raids by contras who, he said, target such facilities for destruction.

Karen Fischer, a graduate student in geophysics at MIT, spent two weeks training Nicaraguans in techniques for identifying geological faults to assess the risk of earthquakes and writing a simple software program for analyzing data, which had previously been done by hand.

Fischer noted that while many Nicaraguans support the Sandinista regime, there are a number of people who criticize it for being either too socialistic or too conservative. “But I was struck by what seemed to be a general tolerance for all points of view,” she said.

Key to Program

The concept for TecNica occurred to Urmann when he attended a conference on Third World development in Managua. He was struck by the large amount of unused or under-used equipment there as well as by the large number of North Americans who traveled to Nicaragua to learn about the country.

The key to the program, he explained was the basic two-week volunteer tour.

“I’d say that two-thirds of our volunteers have no history of political activism,” Urmann said. “They just want to do something meaningful to help others.”

Since the first tour in 1983, TecNica has sent about 180 volunteers to Nicaragua. This year the group has scheduled 12 more tours.

Urmann said the group intends to expand its efforts to other developing countries.